Turkey’s Neo-Ottoman Agenda in Africa

Ankara means to become a leading power. Its long-term strategy is starting to bear fruit, at the very moment that France, Russia, and China are reeling.

NOTE: As we have for many years now, we project that Japan, Poland, and Turkey are not only rising regional powers but will play a greater role on the world stage by mid-century than Russia and possibly China. “Sultan” Erdogan is progressing well toward that goal. — RDM

by Ronan Wordsworth

February 17, 2025

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan wants his country to reclaim its status as a major, or at least regional, power. Embodying an ideology often referred to as neo-Ottomanism, he envisions a Turkey that is more powerful in the lands the Ottoman Empire once controlled – not just the Middle East but North and Central Africa too.

This goal will necessarily require the advancement of Ankara’s Islamic worldview to boost its religious credentials. But it will also necessarily bring Turkey into competition with Saudi Arabia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates, all of which have the same ambitions that, crucially, demand greater engagement in Africa.

Put simply, the path toward a neo-Ottoman empire will inevitably take Ankara through Africa.

Somalia offers a key lesson in Turkey’s Africa strategy. Turkey’s largest foreign military base is housed in Somalia, and Turkish troops have been involved in training the Somali army since 2010. Last year, they signed an official defense pact, as well as an agreement for joint exploration and exploitation of oil and gas deposits off the Somali coast.

Turkish naval vessels now patrol the area for pirates, and some drilling work has commenced. As important, Turkish products are now readily available in Mogadishu, a strategically located market in the increasingly important Indian Ocean basin. Meanwhile, Ankara has established Turkish cultural and Islamic centers and schools and has provided much-needed humanitarian aid.

Two decades of gradually developed influence is starting to bear fruit. Turkey’s presence in Somalia has begun to open doors in West and North Africa that have recently been shut to the West, allowing Ankara to become the region’s new economic benefactor.

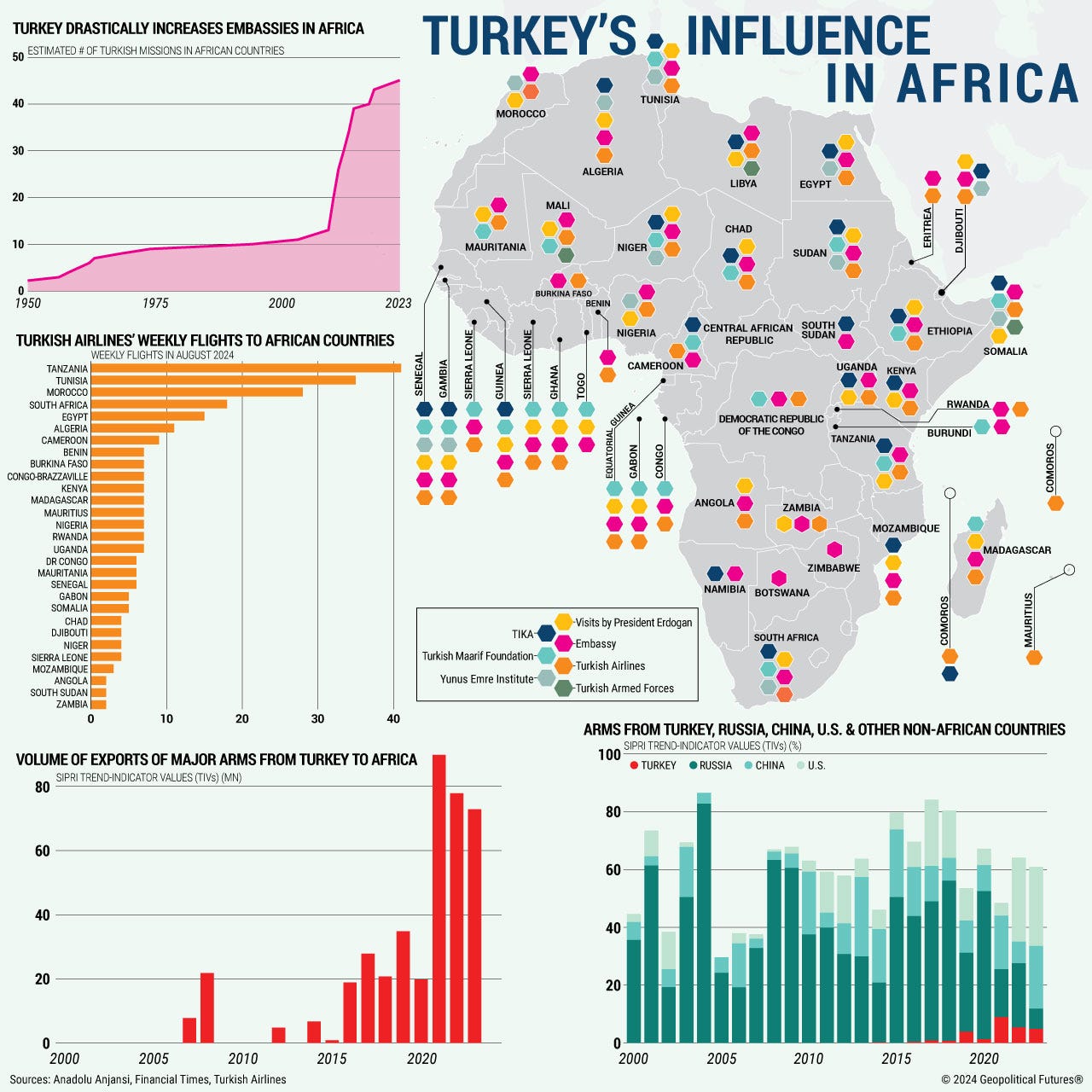

The Somali blueprint illustrates a three-pronged approach to Africa: diplomatic, economic and security. Since Erdogan came to power in the early 2000s, Turkey has prioritized African diplomatic outreach, opening more embassies on the continent than any other country. Erdogan has personally visited 31 African countries on official visits as leader, developing personal relations with ruling parties, but he has always focused on the Muslim-majority countries, where he can talk up his country’s Islamic bona fides.

Turkish Airlines now flies to more African countries than any other airline, and the government provides vast amounts of humanitarian and development money to many African nations to cover infrastructure, education and energy projects and to provide food and health care. Meanwhile, Turkish dramas are widely watched in places like Ethiopia, where hundreds of Turkish businesses now operate, and Turkish-affiliated schools and mosques are frequently constructed. (The Maarif International Schools have been an especially useful source of soft power. Affiliated with Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party and operating 175 campuses in 25 countries, the schools advance Turkish narratives and a Turkish-centric vision of Islam.)

Economically, Turkey’s relationship to the continent has long been defined by trade. Indeed, Erdogan has long seen Africa as a valuable export market for Turkish industrial goods. From 2004 to 2024, trade with Africa increased nearly tenfold, growing from a value of $5.4 billion to roughly $50 billion and covering manufactured goods such heavy and agricultural machinery, chemicals, auto parts, steel, electronics, textiles and raw materials.

In the intervening years, Ankara has signed dozens of trade agreements with individual countries and regional groupings, including the Economic Community of West African States. The Alliance of Sahel States, which comprises countries that have recently turned away from the West and toward Russia, also has very good relations with NATO-ally Turkey.

But the relationship has recently evolved into something more as Turkey becomes more involved in infrastructure projects. Unlike China, which often directly funds these kinds of projects, Turkey tends to implement them through contracts with large African lenders like the African Development Bank. In this way, Turkey avoids accusations of debt-trap diplomacy.

Erdogan boasts of $71.1 billion in projects awarded to Turkish companies under the Turkish Contractors Association since 2021. Existing projects include roads, airports, hospitals and government buildings such as the Modjo-Hawassa Highway in Ethiopia, an international airport near Dakar in Senegal, a railway in Tanzania, conference centers for the 2019 African Union summit and a new national airport in Niger.

Ankara has also been increasingly involved in energy projects, predominantly oil and gas exploration and extraction through the state-owned Turkish Petroleum Corporation. In addition to the offshore developments in Somalia, it participates in projects in Algeria, Libya, Nigeria and Sudan. And it’s begun to dip its toes in renewable energy projects and power plant construction too.

Another important economic facet of Turkey’s influence in Africa is the defense industry. Turkish drones have become highly sought after in many countries, especially around the Sahel, where they are able to cover large areas of open space that central governments typically have little access to. Initial contracts with Morocco and Algeria in 2021 have grown to include Senegal, Nigeria, Niger, Togo, Chad, Mali, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Morocco, Libya, Egypt, Tunisia and Angola.

Arms sales are similarly important. Turkey has been one of the main winners of Russia’s struggle to supply arms to the continent. Defense contractors increased their sales 29 percent in 2024, supplying military equipment such as armored vehicles, firearms, ammunition, artillery and naval vessels. Turkey’s biggest defense exporters include Baykar, Turkish Aerospace Industries, ASFAT, MKE and ARCA.

On the security front, Turkey has steadily expanded its footprint with several initiatives, particularly training programs, that cover counterterrorism, intelligence and peacekeeping, the establishment of military academies and training centers, and hosting joint exercises. For years, Turkey has assisted Nigeria in fighting the Boko Haram Islamist movement, helped stem the flow of illicit arms, and supplied over $5 million to Mauritania and the G5 Sahel to combat Islamic insurgencies.

This steady expansion has positioned Turkey to benefit from the current state of affairs in West Africa. Several countries have kicked out French troops stationed on their borders, U.N. missions have been expelled, and the U.S. has shown less and less interest in the region. (There’s no reason to believe the new Trump administration will change course.)

The resulting power vacuum first allowed Russia to gain a foothold through the Wagner Group, and now Turkish private military contractors, primarily SADAT, are following suit as Wagner suffers setbacks. SADAT offers a similar value proposition: security in exchange for access to minerals. Importantly, SADAT is closely tied to Turkey’s National Intelligence Organization (and to Erdogan himself) through its founder and former general adviser Adnan Tanrıverdi. The group’s standing thus allows it to operate as an agent of foreign influence while giving it a degree of plausible deniability.

Turkey hopes to parlay its successes in Libya into a wider campaign of influence. To that end, Turkish intelligence and the Turkish military have formed deeper cooperation with the Alliance of Sahel States now that France is gone. Turkish intelligence has established a significant presence in the landlocked nation of Niger, a country that could serve as a strategic hub for larger Turkish ambitions while allowing troops to be stationed there. This explains why Turkish leaders have been engaging more with Niger by, for example, supplying military hardware and resources requested by the junta when Western countries refused.

Drones and arms have been used as diplomatic “carrots” to leaders potentially under Western sanctions to secure Turkish influence and long-term arms supply contracts. In conjunction with Turkish government overtures, these moves have opened new markets for the Turkish defense industry — all of which jibes with Erdogan’s goal to expand Turkish defense sales. Expect similar moves going forward.

Turkey’s multifaceted approach to Africa is already starting to see returns. Trade has been markedly increased over the past decade, as has security cooperation — private and public alike. Though Ankara’s involvement could eventually cause a clash with the West, so far it is trying to portray itself as a neutral alternative to China.

The United States will likely go along with Turkey’s strategy: it undermines Russia, creates competition with China and pits Turkey against countries like Saudi Arabia and the UAE with similar designs in Africa. That’s a win all around…at least for now.

A new Ottoman empire is a far way off, but for now Turkey is making meaningful progress toward its goal.

Erdogan is the MB with a suit on, has always been my understanding. The largest mosque in the Western Hemisphere was built by Turkey (remember Obama and Erdogan photo op?) 40 miles from the White House, in Maryland.

As I read this, I could not help but think about what ramifications arise from Turkey's membership in NATO?