Futurism and Traditionalism

In looking to the future, do we also need to look to the past?

This essay is free, but with Premium Membership you get MORE. Join today.

NOTE: On this 44th anniversary of the first Space Shuttle launch, we take a moment to consider the future. This essay by the ever-brilliant Peter Hague addresses some of the deeper issues we should consider as we race toward that future…and as we contemplate how that future was needlessly stolen from us for half a century. — RDM

by Peter Hague

April 12, 2025

The problem with talking to people about the future is that most of them don’t really, deep down, believe it exists. If Thursday is more or less the same as Wednesday, if the routine of one week blurs into the next, it is easy to simply live in an ever recurring present. I have a very busy work and family life, and I can empathise - there is always plenty to think about and do right now, without considering what the world will be like decades or even centuries hence.

But the future is important, and is influenced by what we do right now, today. My writing here and elsewhere is aimed at rallying people to the cause of creating a solar system scale civilisation, where trillions of humans could enjoy a material standard of living reserved for the ultra-rich today. A civilisation whose energy budget and industrial capacity allows it to explore frontiers of physics not accessible to us and to expand to other solar systems. One which permits a diversity of cultures and ways of living that cannot be numerically supported by a single planet civilisation. An alternate future where our species stays confined to this planet is one of at best stagnation, and at worse disaster. What are you doing in the present to take us to the better future?

In the same way people tend to disregard the future, they also often disregard the past. If referred to at all in political debates, it is usually just historical caricatures used to bludgeon the other side - typically by comparing them to the Nazis. Disinterest in the past leaves people without many historical analogies to call on. The past is either a mythology used to vindicate present actions, or just an extension of the endless present. Children have to have it explained to them that their grandparents did not grow up with iPhones, for instance. It is always a conscious effort to understand change over human lifetimes.

When The Present Killed The Future

The counterculture of the 1960s was a movement that fixated particularly on the current moment, primarily in order to dispense with the past. The baby boomers, trying to break free of the staid environment of the 1950s, wanted to break down pretty much all things old and create a new society. But the transformation they unleashed also accidentally sabotaged the future.

The Apollo program represented a chance for a continuous expansion of humanity into the solar system, but as historian David Portree describes any funding for activities beyond the initial Moon landings themselves was brutally cut in the FY1968 budget in the aftermath of the Apollo 1 fire, and they were following public sentiment when doing so. The Moon landings were never particularly popular at the time, only achieving majority approval around the time of the first landing, and over time there were increasing attacks on the program from the perspective of social justice - such as civil rights leader Ralph Abernathy turning up to the launch of Apollo 11 with a sign reading “$12 a day to feed an astronaut. We could feed a starving child for $8”, Gil Scott-Heron’s tiresome “Whitey on the Moon”, and Kurt Vonnegut grumpily denouncing the cost as a theft from the poor on CBS News.

The argument was akin to medieval peasants demanding that cathedrals not be built because at any point in time, the materials and labour could be used to build houses for those who need them. If such logic were permitted at the time, there would simply not be any cathedrals anywhere. Of course, for a generation that cared less for the past than perhaps any other, this wouldn’t be an issue. If there is no real sense of time, there is only the immediate allocation of resources to whatever issue occupies your mind at the moment. History doesn’t matter and neither does the future. Just now.

In late 1969, the philosopher Ayn Rand gave a lecture entitled Apollo and Dionysis in which she compared the great rational achievement of the Apollo 11 landing with the hedonism of Woodstock, to the withering scorn of the latter. In it she captured the cultural mood which stalled the space age for decades. She states:

Their hysterical incantations of worship of the now were sincere. The immediate moment is all that exists for the perceptual-level, concrete-bound, animal-like mentality because to grasp tomorrow is an enormous abstraction, an intellectual feat open only to the conceptual—that is, the rational—level of consciousness. Hence, their state of stagnant, resigned passivity. If no one comes to help them, they will sit in the mud. If a box of Cocoa Puffs hits them in the side, they'll eat it. If a communally chewed watermelon comes by, they'll chew it. If a marijuana cigarette is stuck into their mouth, they'll smoke it. If not, not. How can one act, when the next day or hour is an impenetrable black hole in one's mind?

This lecture is worth listening to or reading and is in my opinion superior to most of her other works (I could not get on with The Fountainhead, on a purely literary level). Ironically it is a robust defence of an expensive government program, which in other circumstances she would despise.

Rand’s rationalism was an odd sort, to her what was rational was self-evident and objective. But as has been argued since Hume, that can’t be the case - rationality has to be defined in terms of passions. Action is rational or not based on whether or not it objectively serves our subjective goals. So for a cathedral-building exercise like Apollo to be sustained, we have to have values which apply across significant time.

When in the 1970s Gerard O’Neill floated proposals for free space colonies, on a relatively short timescale, the cultural change of the previous decade and the success it had in demolishing the Apollo program made the vision impossible on the timescale proposed, and until recent times this was the last time the notion of large scale space colonisation really entered mainstream consciousness. The future was science fiction, and we in the eternal present would never get there.

With the rise of SpaceX that has changed on a technical level, even if the cultural argument has not been won yet. It is possible to show, if people are open to it, the possibility of significant change in their lifetimes - and bring back a tangible notion of the future in space.

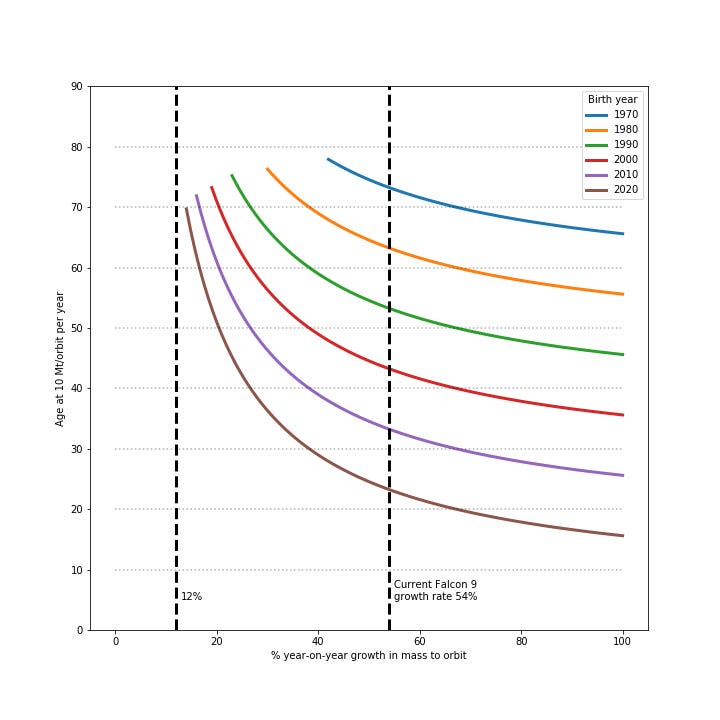

For instance, estimating 10 million tonnes of mass on orbit per year as being a true interplanetary society (and that doesn’t necessarily mean it all comes from Earth, or even that its all in Earth orbit, just useful mass in some orbit) then extrapolating the current growth rates forward, I can plot at what age each cohort would expect to see that future arrive. Even if the rate of mass growth drops off, people reading this still have a decent chance to see it happen. It’s a future that will become your present.

From a purely selfish point of view, we do want to be around to see this future - and hopefully be young enough to take advantage of them. But seeing ourselves as just part of a chain of people extending from the past to the future, this surely isn’t the limit of our concern.

Our Footprints In History

My grandfather on my fathers side was born in 1915. He grew up in moderate poverty, had access to only rudimentary medical care, and had rickets as a child. Still, he lived until 2006 and got to watch 6 grandchildren grow to adulthood. My own youngest son was born 100 years later - coincidentally almost to the day - in 2015. If he had no benefit from the intervening century of advances in nutrition and medicine, he could still expect to live until 2106. The children we know now are future residents of the 22nd century, their lives in that century will be impacted by our actions now, and their memories of us will influence their views and actions.

We will of course all be forgotten in time - but it takes quite a lot of time. Lets say that, conservatively, for a meaningful memory of me someone has to know me up to at least 10 years of age, and be able to think back to the things old (Great-)Grandpa Pete used to say. According to the UK Office of National Statistics actuarial tables for 2022 I, as someone who was 41 in that year, should expect to live another 39 years after then taking me to 2061. A descendant born in 2051, perhaps living 10 years longer due to improvements in medicine, would then still be around in year 2141. This is a useful intellectual exercise and I encourage you all to do it.

These are timescales over which we can expect the world, and the solar system, to radically change. Just a few examples of how it may:

Regardless of how skeptical are you of the transformative potential of AI, few I think would argue it won’t change society radically by 2100, and most would agree it will upend things a lot sooner. What advice would you give to children who will live in this new world? What values would you impart to the machines? Think fast.

A combination of the demographic transition and increasing spaceflight capability will mean that, at some point in the back half of this century, the rate at which people migrate off Earth will outstrip population growth. Which of these two effects drive the crossover most is down to us.

We will have to deal with whatever the effects of climate change may be. Are we going to choose a sharp drive to Net Zero, some form of geoengineering, or just ignore the problem and take it on the chin? There is a lot of histrionics about this but our current generation is going to have to make decisions which people who you know will need to deal with the consequences of.

If the Breakthrough Starshot project or similar succeeds, we will send probes to Alpha Centauri and other nearby solar systems and receive data back from them. We will know if any of the worlds around these stars bear life, or can support human civilisation, and have to make choices about sending people.

Various transhumanist technologies - brain-machine interfacing, human germline modification, life extension - will come to maturity within decades. With a generation or two the descendants you influence might not still be what we think of as human. What would you want to teach such a being?

This logic does not just apply to your own offspring. Many people will not have children but still will influence others who will outlast them. We all forge the future, through deliberate action or otherwise.

If we hope to influence the future though, then those living in future times must to some extent care about their own past.

What I’ve Done Today

We live our lives under a ticking clock, if we bother to hear it. Our time here is long in that we, and the memories of us that echo after us, can span enormous societal and technological changes, and at the same time short as it is easy to let the days, the weeks, and the years slip by repetitively until you find yourself wondering where they went. It’s good to be more mindful, and in giving that advice I should myself account for how I am spending my time.

This weekend I have been working on the website for my Penny For Space campaign. Its an effort to ask the UK government to commit one penny out of every pound of their spending to space efforts. I don’t believe that the private sector here is yet capable of leading the effort and so we need to make the case for state funding, and people I have spoken to in the industry here agree. I have some art for this provided by Daniel Ramer and am preparing for the government to review the petition I have submitted and put it online to start more widely publicising the campaign.

Also, before settling down to write this piece I took my family to see a castle which is almost 900 years old. It was modified and extend over the centuries which it was used, and now stands as a monument to our medieval history.

To a wider solar system civilisation, we will be an ancient people. We will be some mysterious progenitors. They will look back at this time perhaps as I experienced the history of the Normans at Castle Rising.

What will they think of us?

— This essay originally appeared at Peter Hague’s ever-brilliant Planetocracy.

I have to say, it's hard for me to take seriously anything from someone who still believes in "climate change."

That said, the gist of this article rings true. There IS a place in this world for aspiration + challenge - it is part of our human psyche. It is what led both to the building of the Cathedrals (for example) 1000+ years ago, with nothing but hand tools and manual architecture. It is also what prompted Columbus to set sail.

The same (or at least similar) motivation is cheering for the underdog stories (e.g., "Miracle" by Disney before it went totally woke-crap, and excellent movie about our 1980 Olympic hockey team).

Being in elementary school in the 1960's, I recall at the time - from "Star Trek" to stories of nuclear powered cars that would run for 20 years on a single pellet of fuel (and so on) - to it all seeming not just plausible, but soon within reach. Recall then we were just 50-60 years from the Wright brothers, and were about to land on the moon. So that pace of progress seemed "normal." Not so much, these additional 50-60 years later.

For a whole host of reasons too lengthy to cover here, we (and the world) lost the script in the 1970's (and since) - despite the advances in computing power.

That said, with this second Trump term, I've sensed - for the first time since the 1960's - that we could be on the cusp of resuming the upward trajectory we enjoyed in the 1950-1960's. That may be the largely unrecognized element of MAGA and Trump's references to "a new golden age."

You need to dig deeper on climate change