Deep Dive: What Peace in Ukraine Will Take, and Why

Donald Trump is committed to negotiating a peace that everyone can live with. The people most upset about it are Western elites.

by Rod D. Martin

February 15, 2025

This week Donald Trump spoke with Russian President Vladimir Putin and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. The aim? Not just a peace both sides can accept in the short term, but one that can actually last.

Neither side is going to be happy. But the Beltway Establishment is already livid. They talk of driving Russia from every square inch of Ukrainian soil, and immediately folding Ukraine into NATO. They don’t talk about the cost either of those things would require.

Russia is in the wrong. Countries shouldn’t conquer territory from one another — the nations of the world actually outlawed that in 1945 — and certainly shouldn’t benefit from their lawless acts.

Nevertheless, Western elites act as though they have infinite Godlike power to remake the world in their chosen image.

They don’t. But they’re very willing to fight to the last drop of Ukrainian blood — and possibly yours also — to “win”.

Trump is not. Not a neocon, not a social engineer, and not an endless interventionist. But he is a humanitarian, and wants to stop the bleeding on terms that actually resolve the problem.

That doesn’t fit the Globalist agenda at all.

How We Got Here: Russia’s Enduring Fear of Encirclement and Conquest, and NATO’s Refusal to Care

For much of the twentieth century, global power revolved around the struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union. That existential conflict defined military, economic, and political alignments across the world, creating a system that, though volatile, clearly structured international affairs.

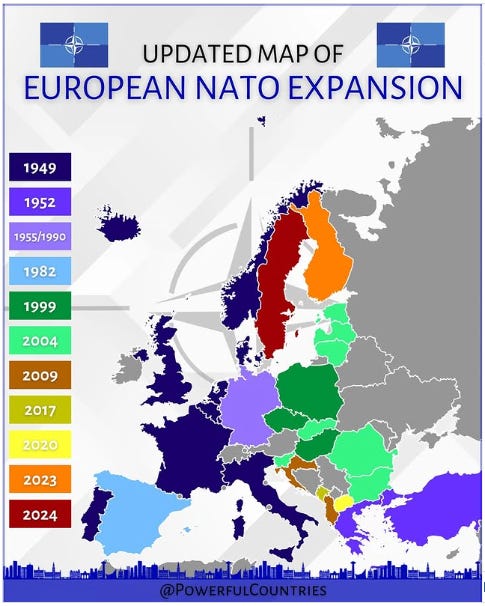

That all shattered in 1991. The Soviet Union collapsed, and with it, Russia lost not only its superpower status but the geographic buffers that had shielded it for centuries. Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltics — once Moscow’s defensive perimeter — became independent (as of course they should have). And wisely or not, the West wasted no time expanding its influence into these territories.

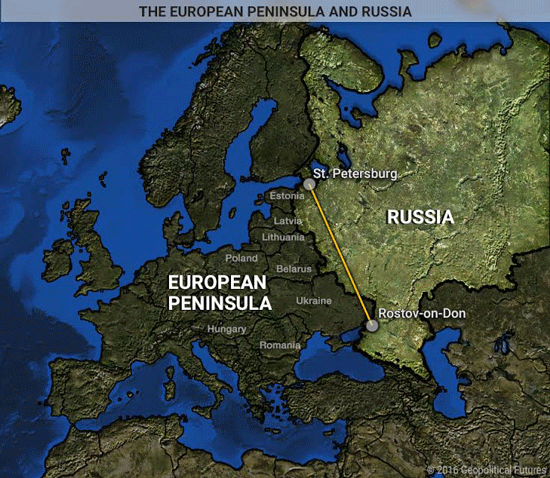

To the United States, this was a natural expansion of liberal democracy. To Russia, it was an existential threat. Russia exists on the North European Plain, a flat superhighway for armies, and has been invaded repeatedly, suffering horrific losses. It has always feared encirclement. Napoleon, Hitler, and countless other invaders have made it painfully clear that Russia’s survival depends on strategic depth — on absorbing the shock of an invasion before an enemy can reach its heartland.

Russia’s fear of encirclement is not paranoia; it is a deeply ingrained reality that has shaped its policies for centuries. Unlike the United States, which benefits from vast oceans as natural barriers, Russia’s western frontier, from the Baltic to the Black Sea, lacks significant natural obstacles, making it vulnerable to attack from European powers. Russian rulers, from the Czars to the Soviets, have all prioritized securing buffer zones as a means of ensuring national survival. I am not suggesting that their methods were in any way acceptable, then or now. But their choices were certainly logical.

Without control over Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltics, the core of Russia itself is exposed to potential aggression from the West. This is why Putin called the fall of the Soviet Union “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century”: it left Russia indefensible in a way it had not been since before the Napoleonic Wars.

Losing Ukraine to the West meant losing that strategic depth. Worse still, it raised the prospect of the German Army (within NATO) being less than 300 miles from downtown Moscow, just as it was at the height of World War II (in which Russia lost 27 million people, vs. America’s 400,000). Western elites can poo-hoo the fear that provokes, but they’re stupid to do so. And as to Germany, it may be a nice country today, but from Russia’s point of view, that could change as quickly as it did in 1914 or 1933.

For Russia, given their 27 million war dead last time, Western armies within reach of their capital represents an existential threat of the same magnitude as an actual nuclear war.

One can argue for or against NATO’s expansion into Eastern Europe. But Russia is correct in saying both the first Bush Administration and the German government promised that would never happen. They feel betrayed, and rightly so, by the Europeans and by both American parties over the course of the 1990s and 2000s. President Clinton especially rubbed their noses in their post-Cold War humiliation (just re-watch The West Wing to see American liberals’ patronizing attitudes at the time).

From Russia’s perspective, the question was “why”? If the Cold War was over and we were all friends now, why should they be treated like a third-class power, and more to the point, why would NATO want to expand toward Russia (or even continue to exist)?

The 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine and NATO’s continued eastward march convinced the Kremlin that Western encroachment was a deliberate attempt to vassalize Russia permanently. Putin’s rise to power was, in many respects, a response to this perceived crisis. His mission was clear: restore Russian power, reassert control over former Soviet territories, and ensure that Ukraine never became a tool of the West.

Putin has pursued that mission doggedly. He’s mostly failed.

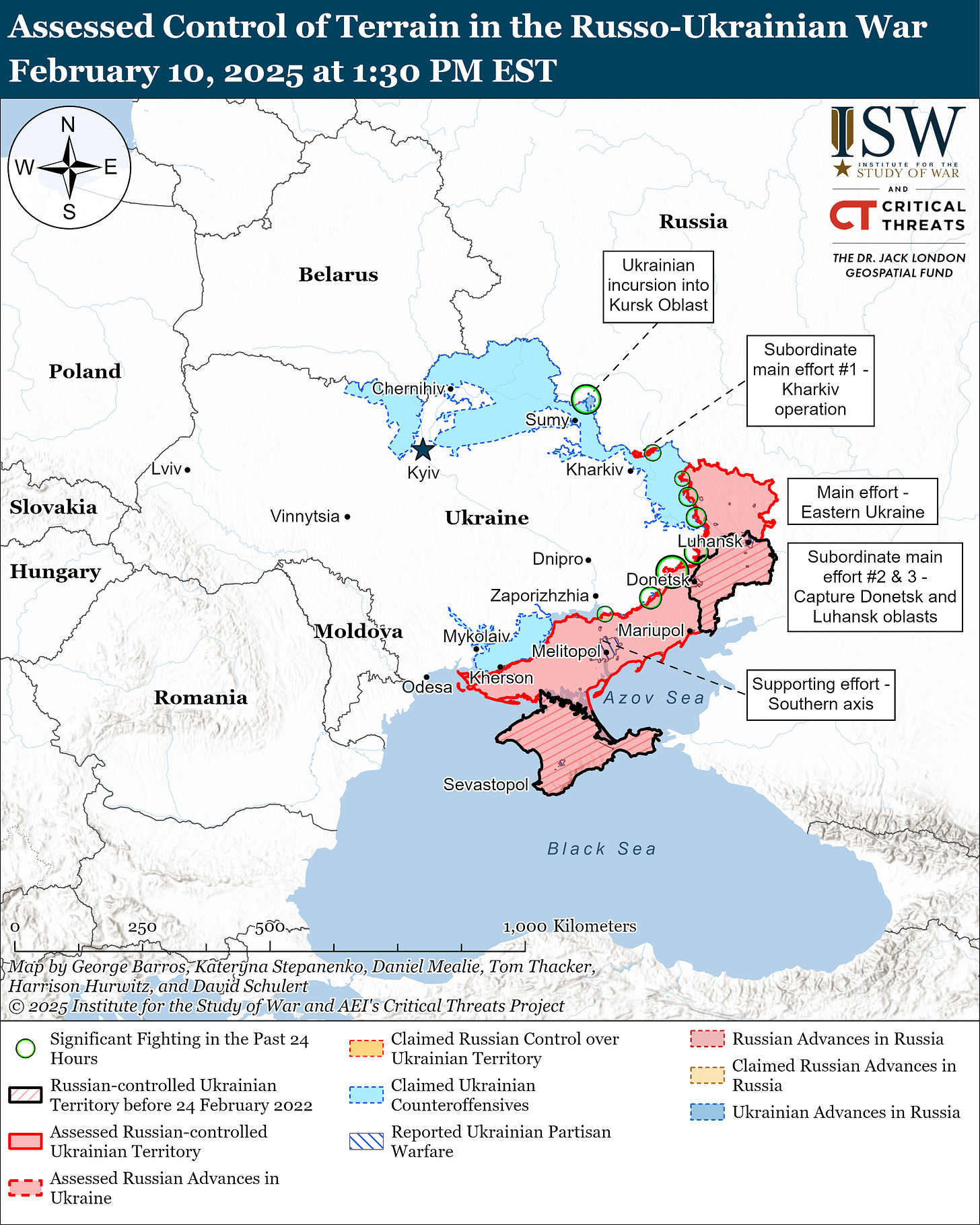

Despite eight years of preparation following its annexation of Crimea in 2014 (to which the feckless Obama Administration did not respond in any useful way at all, despite Clinton’s security guarantees solemnly given 20 years before), Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine has been a strategic disaster. The Kremlin had envisioned a swift victory, a government collapse in Kyiv, and a Ukraine brought firmly back under Moscow’s influence.

Instead, Russia has captured only a fraction of Ukraine, suffered staggering casualties, and found itself in a war of attrition that has sapped its economy, military strength, and demographic future. Sanctions have weakened Russia’s economic leverage, while military setbacks have exposed the limits of its conventional forces.

The world now realizes what I told you for years before the war: Russia’s military, and Russia itself, is a Potemkin Village. Only the Beltway Establishment denies this now.

Ukraine’s importance to Russia is threefold:

First, it serves as a geographic shield. The vast Ukrainian plains historically forced invaders to stretch their supply lines before reaching Russia’s industrial and political heartland. Napoleon’s army suffered from overextension in these plains, as did Hitler’s Wehrmacht in World War II. Without Ukraine, Russia’s western border becomes indefensible, forcing it to rely on Western goodwill it has every reason to distrust.

Second, Ukraine was an integral part of the Soviet economy, providing critical agricultural, industrial, and energy resources. The Donbas region in particular was one of the Soviet Union’s industrial powerhouses, and losing it meant losing economic self-sufficiency.

Finally Ukraine was previously home to Russia’s Black Sea Fleet in Crimea, a key naval base giving Russia access to the Mediterranean. Without that access, Russia is reduced to a regional power at best.

I’m about as excited about the idea of “Russian power projection” as you probably are. But Russia has long depended on its access to warm-water Black Sea ports to exert influence beyond its borders. The prospect of Ukraine aligning fully with NATO was and is, from Moscow’s view, a direct threat to its ability to maintain influence in the Black Sea, the Mediterranean, and beyond. For this reason, Crimea was not simply annexed out of nationalist sentiment but because it remains essential for Russian naval power.

So the 2014 Ukrainian color revolution was the breaking point. Unlike the Baltics, Ukraine was not just another post-Soviet state — it was central to Russia’s historical, economic, and strategic calculus.

This entrenched fear is what drives Russian foreign policy and explains why Moscow has been willing to bear immense economic and military costs to maintain some control over Ukraine. Ukraine in NATO is Russia’s equivalent to the Cuban Missile Crisis. And no peace other than conquest — of one country or the other — is possible until the West gives that fact its due.

Could Russia Shatter Like the USSR?

At the extreme end, the danger to Russia is that it might come apart at the seams. Indeed, there’s a lot of reason to believe that China and the West pushed them into this war, one which could have been avoided through negotiations on better terms than we’re discussing today, to bring about that exact result.

But it doesn’t really matter what I believe. It matters that Russia believes it: both that it could happen and that that’s the West’s aim.

And be honest: why shouldn’t they?

Regardless, as the war grinds on, the possibility of Russia fragmenting into multiple new countries — potential new Chinese satellites, EU members, and NATO arms customers — has become more plausible. Historically, when Russian governments lose wars, they collapse — this happened with the Czar after World War I and the Soviet Union after Afghanistan. Don’t think the Kremlin has forgotten.

Regions like Siberia, the Caucasus, and the Russian Far East already have growing independence movements. There are lots of outsiders who’d love to exploit that, and in some cases already are.

China, now Russia’s dominant economic partner, is quietly but ruthlessly exploiting Russia’s weakness. It promised Putin “an alliance without limits” a week before he went to war, only to stay neutral. By purchasing Russian oil at much-below-market rates and forcing Moscow to conduct trade for its desperately needed imports in yuan and gold — not rubles — Beijing has effectively turned Russia into a junior partner, if not a colony.

Meanwhile, Beijing is watching how Western military aid is reshaping modern warfare, lessons it may apply in a future conflict over Taiwan, while NATO tests new weapons and strategies with no human cost to itself. If Russia emerges weakened but still holding territory, it may embolden China to pursue similar tactics in the Taiwan Strait and beyond. Conversely, if Russia collapses under the weight of prolonged war, Beijing will waste no time expanding influence over whatever’s left.

The usual suspects gain a lot from the Forever War.

Stalemate and Casualties

As the war grinds on, neither side having any realistic prospect of victory, both Ukraine and Russia have suffered catastrophic losses, with casualty numbers that rival some of the bloodiest conflicts of the 20th century. Estimates are hotly contested, but Russia’s total casualties may be as high as 800,000, while Ukraine’s losses likely surpass 500,000. These figures include regular military personnel, conscripts, and mercenaries such as those from the Wagner Group, as well as Ukrainian territorial defense forces and foreign volunteers.

The human cost of this war extends beyond the battlefield. Millions of civilians have fled their homes, seeking refuge either abroad or within their respective countries. Nearly 7 million Ukrainians have fled the country since the war began, with another 5 million are displaced within Ukraine.

Russia has also seen an exodus of over 1 million people, consisting not only of draft-dodgers and political dissidents but also a significant share of the country’s highly skilled professionals, leading to a long-term economic and demographic drain.

Can Either Side Sustain These Losses?

For Russia, sustaining such immense casualties has been easier due to its much larger population of 143 million, its ability to mobilize reserves, and its authoritarian control over dissent. Despite growing public discontent, Russia’s leadership has continuously replenished its forces through forced conscription, recruitment of prisoners, and aggressive propaganda aimed at maintaining domestic support. However, these tactics come at a cost — an aging population and ongoing emigration mean Russia is sacrificing its future workforce to prolong the war.

Ukraine, with a much smaller pre-war population of just over 40 million and far higher emigration, faces a greater challenge. While Western support has helped mitigate some losses by supplying advanced weaponry and intelligence, it has not included ground troops.

Kyiv’s ability to sustain these casualties depends on continued international aid and maintaining morale among its people, but it also depends on not running out of people. Ukraine has enforced strict conscription policies, including extending the draft to older age groups, but as casualties mount and fewer young men remain to fight, the long-term sustainability of Ukraine’s war effort is increasingly in question.

Despite the staggering losses on both sides, neither country has shown a willingness to back down. The war has become a grinding battle of attrition, where victory will likely go not to the side with superior tactics but to the one that can outlast the other in sheer manpower and resources.

Neither country can afford it. Both faced demographic collapse even before the war. Both are now bleeding out. And yet, if Russia just pulls out, not only is its government likely to collapse, the entire Russian state might shatter. And even if not, the war and all its losses will have been for nothing.

Something’s Gotta Give: Trump’s Talks with Putin and Zelensky

I have focused this essay far more on Russia than Ukraine because Ukraine has very limited say in whether or not the war ends. Despite early hopes, it can’t beat Russia. Its Kursk Offensive, while admirable, is at most an effort to hold swappable territory at the peace table. It can’t simply stop fighting without surrendering. Losing outright would reduce it to a Russian colony.

So the issue is existential for both countries. But after three years of war, Russia — though stalemated — clearly has the upper hand. So if we want the war to end, our choices boil down to two: an American invasion, with the prospect of mass military casualties and possibly nuclear war; or tailoring a solution that both parties can live with.

That’s the reality the Uniparty refuses to acknowledge, and that Trump the deal-maker clearly sees.

This week, President Trump, engaged in direct calls with both Putin and Zelensky, to the great hysteria of European leaders and Beltway elites (they compared Trump to Chamberlain, which is odd, since there’s not a Churchill among them). Trump’s approach diverged from previous Western leaders’ insistence on Russia’s total withdrawal — surrender — as a precondition for peace. Rather, he acknowledged the harsh reality: Ukraine cannot push Russia out of all of its territory, and continuing the war indefinitely would be catastrophic for both nations.

And it’s not just the human cost, or the growing devastation of Ukraine. It’s also the risk of entrenching a cycle of war, where neither side secures a peace they can live with so both are constantly looking for a rematch. Sadly, ending the war in a way that ensures long-term stability is more vital than achieving an ideal outcome.

Trump’s proposed settlement centers on a Finlandization model1 — one where Ukraine remains a sovereign state but commits to permanent neutrality. U.S. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth reinforced this position, outlining a plan in which:

Ukraine would not join NATO, removing a key Russian pretext for further aggression.

Russia would withdraw from most occupied Ukrainian territories, significantly rolling back its invasion.

Crimea and certain parts of the Donbas would remain under Russian control in some form, reflecting the military and political realities on the ground.

Ukraine would receive long-term Western security guarantees but would not host permanent U.S. or NATO bases.

This approach would deny Putin total victory but also prevent his total humiliation, ensuring Russia has an off-ramp to end the war without escalating it further. For Ukraine, this deal would safeguard sovereignty while minimizing future risks, avoiding an agreement so fragile that it simply invites future Russian revanchism.

Above all, it buys time. There may not even be a Russia in another twenty years.

Trump sees a stark humanitarian necessity to end the war. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers and civilians have died, entire cities have been reduced to rubble, and millions have been displaced.

It is an unrealistic luxury to believe that wars are ended by morality — they are ended by pragmatic choices that recognize when enough blood has been spilled. The Neocons demand that outright moral victory, but are they willing to pay the price America paid in World War II or the Civil War to get that “unconditional surrender”?

Are you?

On Trump’s terms, there’s a deal to be had. Anything else will require that one or the other country surrender. So the war will drag on for years, accomplishing nothing but death and destruction.

Conclusion: Stability and Peace Over Perfect Justice

Russia thought it could take Ukraine whole in three days, at most a week. It gambled and lost, and Ukraine fought harder and smarter than anyone expected. But wars do not end on principles alone — they end when the cost of continuing outweighs the price of compromise.

As peace talks gain traction, land will be swapped, Ukraine will likely accept Finlandization, and Russia will retreat from key areas while trying to salvage its national dignity and some reasonable defense perimeter. No matter the outcome, it will be in a vastly worse position than it was before the war. But backing it into a corner would be even more foolish than letting Ukraine fall.

This war will not end because one side was proven right. It will end because both sides must live with the outcome rather than fight again.

Trump is committed to making that deal. If he does, it will be every bit as Nobel Peace Prize worthy as Teddy Roosevelt’s deal with Russia and Japan.

It should not be lost on anyone that Finland itself is no longer “Finlandized”, having joined NATO in reaction to the war. Nevertheless, that approach enabled Finland to maintain its freedom for the entire Cold War, following immediately after two wars with Russia and just a generation since the country had been an integral part of the Russian Empire for centuries. If Ukraine cannot be admitted to NATO without provoking a general war, then this is the best possible outcome.

Excellent piece. I read it twice to make sure I didn’t miss what I was looking for. And my eyes are blurry from an infection. So if a correction is in order, I’ll take it.

You mention the ‘color revolution’ in 2014. But you fail to attribute the blame for this where it belongs. On the Obama Administration. And the CIA. Who deposed a duly elected government because they didn’t like that the elected leader was aligned with Russia. The direct meddling of the US, as has happened so many times, laid the groundwork for the war.

In addition, 20+ years of unnecessary NATO expansion provided the underlying fuel for the conflict. This war was set up by the US. It has been funded by the US. And the US has provided technology and (unacknowledge) boots on the ground.

Putin may have lobbed the first mortar. But the reality is the US did everything to initiate this conflict, except fire the first shot.

I’ll leave the dozens of biolabs for another day.

Thoughtful and thorough article. Excellent. Thank you.