How Dangerous Is Japan’s Remilitarization?

New tensions have expedited Tokyo’s long-term plans.

January 11, 2025

Japan’s military had a busy 2024, and all indicators point to an even busier 2025. The year was punctuated by an announcement from Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba that Tokyo would increase military spending, engage in more multilateral military exercises and sign additional defense agreements with regional allies – all in an effort to deter aggression from China, Russia and North Korea.

Geography largely explains why Japan is often at odds with its neighbors. The Japanese archipelago blocks the Korean Peninsula and the southernmost point of Russia from direct access to the Pacific. It does likewise for the northeastern Chinese regions around Shanghai. More, Japan itself has few natural resources – it has to import them from elsewhere – making it disproportionately reliant on the same sea lanes. Historically, this reliance on others for resources has compelled Japan to seek territory by force in mainland Asia, creating historical grievances that exist even today. Add to this the fact that Japan is Washington’s most steadfast ally in the Asia Pacific, and you can see why it butts heads with its neighbors.

And tensions are certainly high today. After Russia invaded Ukraine, Washington built a coalition of countries willing to put sanctions on the Russian economy – in which Japan was an early participant. One of the ways Russia responded to the sanctions was to increase military posturing in the Pacific, including exercises on the disputed Kuril Islands, joint maneuvers with China’s military and sending aircraft over the Bering Strait. (The Kuril Islands, which are disputed by Japan, are vital to Russia’s ability to maneuver from Vladivostok to the Pacific.)

China, for its part, has increased its military presence in the South China Sea and its posturing toward Taiwan. Beijing depends on maritime access, especially in the South China Sea, to support its export-oriented economy and to maintain its position over Taiwan. (This is to say nothing of the potential resources that can theoretically be mined in the South China Sea.)

Then there is North Korea, whose missile tests tend to take place over the Sea of Japan. The government in Pyongyang has allied itself with Russia, sending troops to the battlefields in exchange for food and electricity. Taken together, these actions remind Tokyo of how vulnerable it is in the region.

This vulnerability likely accounts for why its military posture has changed so dramatically throughout history. For much of its history, Japan has used its island geography as insulation against threats. However, there are two major exceptions to this rule: the invasion of Korea in the 16th century and the expansionism leading up to World War II, both of which were precipitated by a perceived scarcity of resources.

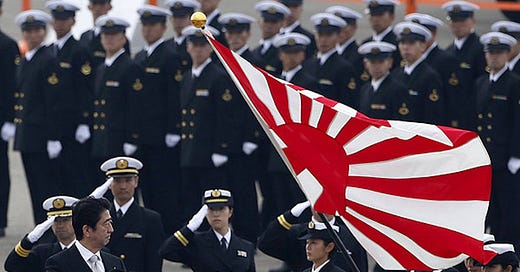

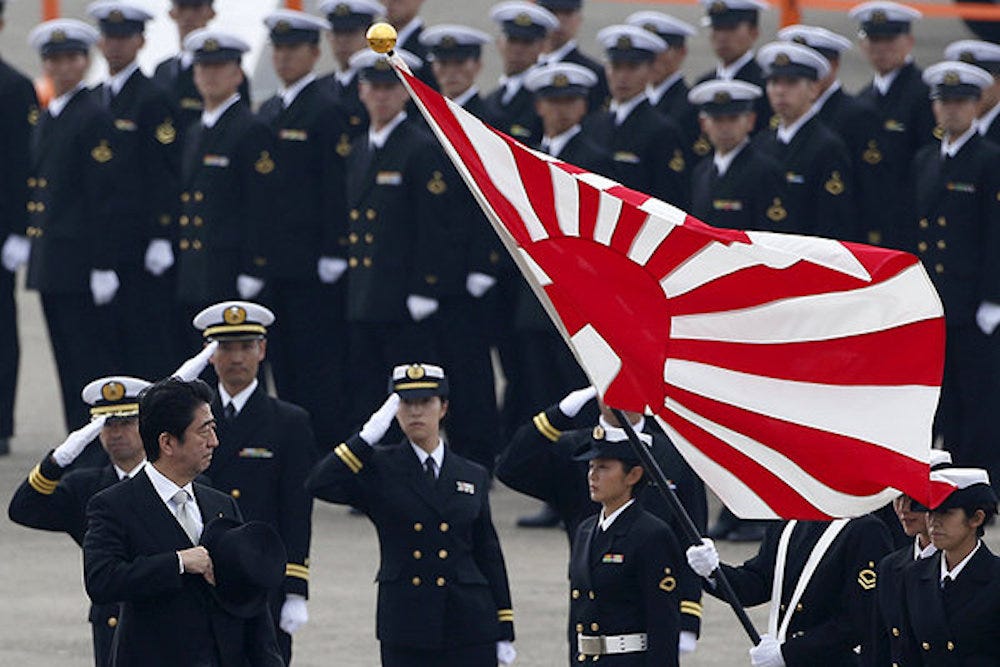

The latter era was characterized by the Japanese occupation of the Korean Peninsula, Manchuria, a large swatch of mainland China’s coast and modern-day Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia and the Philippines. After World War II, Japan was forced to demilitarize, and elements of pacifism were enshrined in its constitution. (Even today, Japan’s military is known as the Self-Defense Forces.)

Tokyo’s close relationship with Washington made it so that it didn’t need an offensive military of its own. But now that the U.S. is trying to reduce its military footprint in certain parts of the world, it wants its allies to assume more responsibility in ensuring stability. Hence the efforts by Tokyo to rebuild its military.

But remilitarization doesn’t necessarily mean aggression. In fact, Japan’s behavior clearly shows that Tokyo is pursuing a policy of denial deterrence, which essentially forces enemies to look at Japan’s military and decide the benefits of attack aren’t worth the costs.

The strategy suits Japan for several reasons. One, the country’s geographic position naturally blocks vital sea lanes. Two, the strategy accommodates Japan’s national security needs without running afoul of its constitutional constraints, which still allow the military to participate in “collective self-defense” with its allies. Three, it lends itself to and benefits from increased cooperation with regional partners.

Japan recently signed a comprehensive strategic partnership with Vietnam, participated in military drills with South Korea and conducted training operations with India, Australia, the Philippines, South Korea, Singapore, the United States and several others.

The fourth and perhaps most important reason is that the numbers do not favor Japan, especially from an offensive position. Its military consists of about 260,000 troops, about 540 tanks, 720 aircraft (including 320 fighter jet), 154 naval vessels with 22 submarines and one light aircraft carrier. For comparison, China boasts 2 million active-duty soldiers with 4,950 tanks, more than 3,300 aircraft, some 370 warships with 60 subs (12 of which are nuclear-powered) and two aircraft carriers. Russia’s and North Korea’s militaries are also much larger.

Japanese demographics are also bad: Its aging population will prevent it from reaching Chinese, Russian or North Korean numbers anytime soon, and recruitment efforts have fallen short of expectations. (Japan was 50 percent short of its recruitment goal for last year.)

Japan has looked to its allies – and technology – to try to overcome these shortcomings. It has a defense agreement with the United States whereby it hosts 55,000 U.S. troops and a U.S. carrier strike group, and the U.S. supplies Japan with weapon systems that are generally regarded as more advanced than the Chinese systems to compensate for a lack of manpower. Japan is also working with Italy and the United Kingdom to develop modern fighter jets to replace its F-2s. And it recently announced joint development and production of Australian frigates to reinforce ties and raise Japan’s naval capabilities.

Crucially, modernizing a military is not without challenges. One of the biggest constraints Japan faces is the value of the Japanese yen, which is at a 38-year low. The government is taking steps to reverse the fall, but doing so will take time. And until the yen gets stronger, military purchases will be all the more expensive. This explains why the parliament has recently approved a budget that will levy a 4 percent tax rate on corporations and a 1 percent rate on personal income to pay for additional defense spending. The prime minister’s goal is for military spending to reach 2 percent of gross domestic product by 2027.

Winston Churchill said that having a large and efficient military acts as a deterrent to foreign forces, noting that “War will be avoided, in present circumstances, only by the accumulation of deterrents against the aggressor.” But the second part of his quote is perhaps even more apt for modern-day Japan: “If our defenses are weak, we must seek allies.”

— This essay originally appeared at Geopolitical Futures.

A very insightful look at modern day Japan.