by Rod D. Martin

January 16, 2004

Historians sometimes ask themselves questions like “How must Queen Isabella have felt when she finally gave permission for Columbus to sail to the New World?”

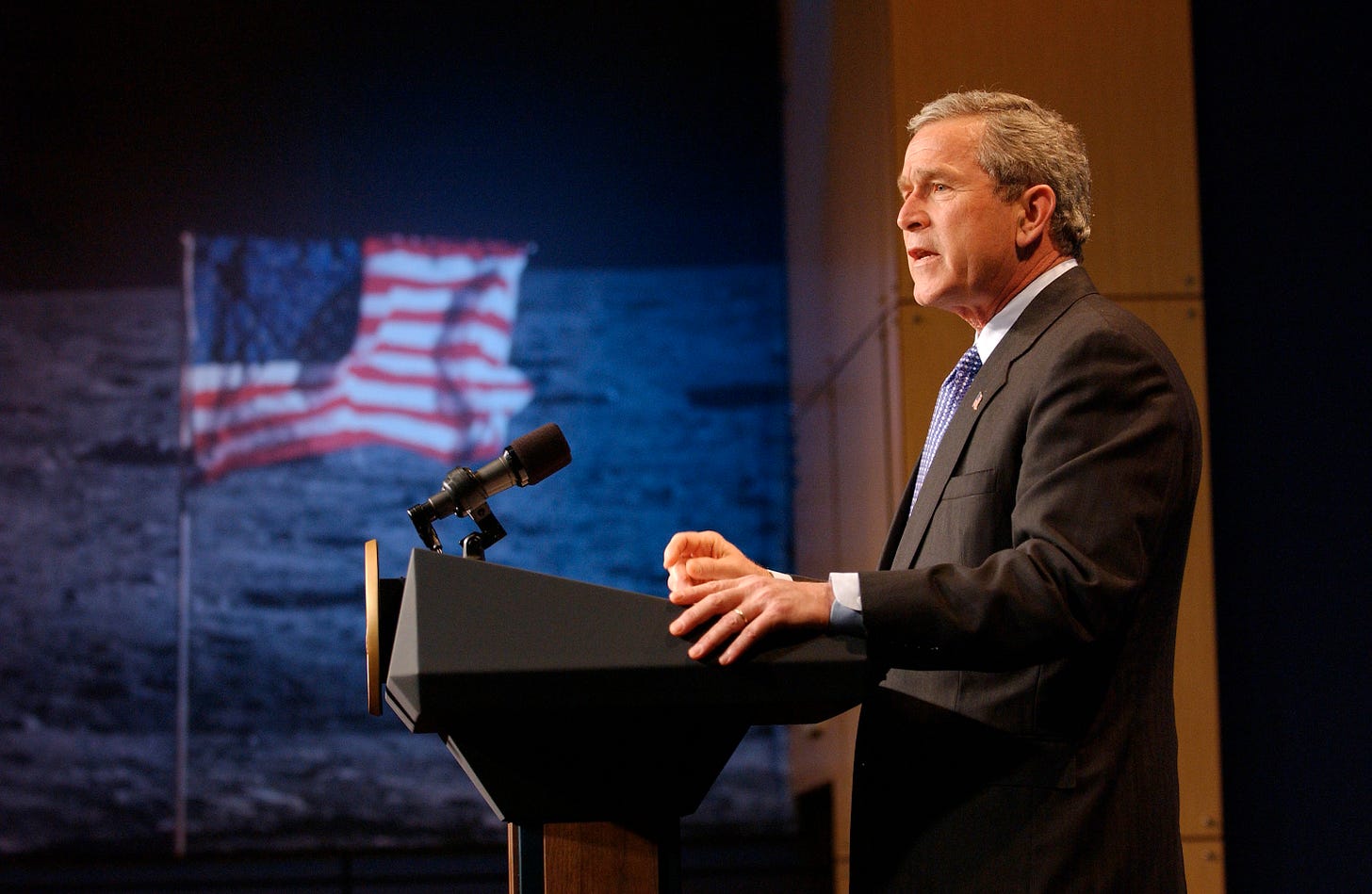

Maybe someday they will ask the same of George W. Bush.

Bush’s vision, announced this Wednesday to an overflow crowd at NASA headquarters, is a vow to expand “human presence across our Solar System”. Said the President: “We will set a new course for America’s space program; we will give NASA a new focus. We will build new ships to carry man forward into the universe to gain a new foothold on the Moon and prepare for new journeys beyond Earth.”

Our Russian and European space allies cheered; so should every American. For the cost of one-tenth of one B-2 bomber (a tailfin perhaps?) per year, the President has set in motion the most dramatic change in NASA’s priorities since John F. Kennedy announced Apollo: a permanent Lunar colony, possibly as soon as 2015, followed by manned expeditions to Mars -- amo…